Fabian Nicieza, Argentine-born American, has been one of the two writers who, in the early 90s, has inherited the legacy of Claremont on the titles of Marvel mutants. In the course of his career, as well as for the House of Ideas has also written for the Acclaim Comics and in recent years is active in numerous publications by DC Comics.

Fabian Nicieza, Argentine-born American, has been one of the two writers who, in the early 90s, has inherited the legacy of Claremont on the titles of Marvel mutants. In the course of his career, as well as for the House of Ideas has also written for the Acclaim Comics and in recent years is active in numerous publications by DC Comics.

Hi Fabian,

thanks for joining us at Lospaziobianco, for this “Special X-Men 50th Anniversary”.

Last year we interviewed Bob McLeod on Kraven’s Last Hunt masterpiece; it is a piece of history of comic books according to all fans like us. When he started answering he told us “I’m an artist, and didn’t pay a lot of attention to that kind of stuff. I concentrated on the jobs I was given, and focused on doing them as well as I could.”

That means that sometimes we love comic book so much that we are not able to see that, even if moved by passion, writers and artists are maybe just “doing” their job.

So… In the recent past you said that you don’t have a special memory of your run on X-Men titles (1992/1995). Would you like to tell us what didn’t work in that working experience? Did you save something good from that period?

There were a lot of things that I don’t think were working creatively at the time for me personally. I think there was little to no subtlety to our approach, which was endemic to the times, but also we fed into that, like giving sugar to a kid then being surprised they get hyperactive.

My working method was very different than the preferred working method of our editor, Bob Harras and my franchise co-architect, Scott Lobdell. We were all friends, but it led to ongoing frustration about how the books were being planned and written. The amount of pressure we were under from Marvel’s then-greedy owners was ridiculous, and every single time we exceeded their sales expectations, instead of saying congratulations, they said, “Give us more.”

So lots of things were exciting, the popularity of the titles, the “rock star” vibe was fun for a while, the money was great and created a solid foundation for my family, but the actual creative work itself was never something I was satisfied with.

Luckily, I got to write plenty of other titles that I found more creatively fulfilling, so it wasn’t constant whining and pain.

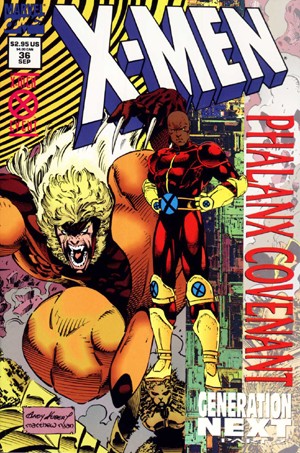

According to fans (and to us) that was one of the gold period of X-Titles (great sagas like Executioner’s Song, Fatal Attractions, Phalanx Covenant, etc.). You and the other writes were free enough to decide what to do in these “crossovers” or the fact there were a few of them working together was a little bit limiting…

According to fans (and to us) that was one of the gold period of X-Titles (great sagas like Executioner’s Song, Fatal Attractions, Phalanx Covenant, etc.). You and the other writes were free enough to decide what to do in these “crossovers” or the fact there were a few of them working together was a little bit limiting…

We did a lot of what we did through little choice of our own. The crossovers sold. They were big events. So the expectation forced on us was that we had to keep doing them. Unfortunately, that creates a forced rhythm to the dance, when you know you have to do a crossover twice a year or whatever, you’re forced to build your pacing to the “big event” rather than to the actual needs of your particular book or characters.

I think the irony comes in having watched our work be denigrated by so many people for years afterwards — fans and professionals alike — including some people who were at the highest levels at Marvel, while always happy to cash the checks they were receiving from reprinting all the material or revisiting nearly every single one of our stories – Third Summers Brother, Age of Apocalypse, etc. – to help fuel their current work.

While you were writing X-Men, Uncanny X-Men was written by Scott Lobdell. Were you planning together directions of histories? Or even the use of single character?

We would trade back and forth. We would each “claim” certain characters for story arcs. For the most part, that worked out fine.

From the “professional” point of view, did that period leave to you something good? I mane, did you have the chance to work “near” other big of comic books, were you able to keep from them a few of their competence?

It left me a lot of good things. I don’t want it to sound like it was all awful or anything, because it wasn’t. It’s just you would prefer, as a career retrospective, than the work you did that reached the most people was the work your were most proud of, but with the X-books, that wasn’t the case for me, that’s all.

We understand that your run on X-Men was more a sort of result of your professionalism more than passion: which kind of feedback you had from readers?

We understand that your run on X-Men was more a sort of result of your professionalism more than passion: which kind of feedback you had from readers?

Well, feedback from readers is a relatively consistent thing. A percentage love your work more than they should, a percentage hate your work more than they should, everyone else is in the middle. I had people waiting in line two hours for convention signing and one would say a specific issue was the best comic they ever read and the guy in line behind him would say, “You suck.”

You learn to take all that with a grain of salt very quickly or it could drive you crazy. For the most part, reaction was always very positive, and frankly, sales bore that out.

What if you had a chance to go ahead without any limit during your X-Men run? Is there something you wanted to do and you didn’t do that you want to tell us?

I have never lived a life of “this is what I would have done” after I’ve left a book. Other writers like to do that, but not me. Whatever it was, for good or bad, is what it was.

Do you think that the basic concept of X-Men (inequality, fear of mutants, etc) was a good one and/or a good excuse to talk about these issues in a comic book?

Yes, I think the theme was touched on by Stan Lee and Roy Thomas, but more fully explored by Chris Claremont. I think it made for very powerful underlying themes to the books and for the characters. Sometimes it’s portrayed more artfully than others, but I think the themes should remain a constant in the X-titles.

Interview conducted by mail and ended on 2013/06/22

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.